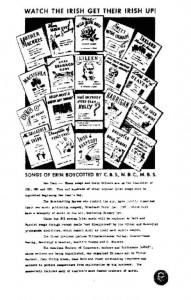

By New Years Day 1941, the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers’ patrimony, nearly every well-known popular song published over the preceding thirty years, had disappeared from the network ether. The NBC broadcast booth at the 1941 Rose Bowl was hermetically sealed off from ambient sounds, lest its microphones accidentally capture the University of Nebraska or Stanford marching bands striking up an ASCAP tune. Listeners-in had to take announcer Bill Stern at his word that the 90,000 fans “were having the time of their life,” when all they could hear was a sepulchral silence. That night, on Eddie Cantor’s show, his latest discovery, Dinah Shore, had to forego her breakout hit, “Yes, My Darling Daughter,” in favor of an arrangement of the public domain “Listen to the Mockingbird.” A number of bandleaders simply gave up their network shows, some because they couldn’t eliminate ASCAP music from their repertoire, and others because they wouldn’t sign indemnity agreements demanded by the networks, who worried that copyright infringement claims would result if a rogue player were to “suddenly interpolate a few ‘hot licks’ of an ASCAP tune into an otherwise perfectly safe number.”

Listeners-in had to take announcer Bill Stern at his word that the 90,000 fans “were having the time of their life,” when all they could hear was a sepulchral silence. That night, on Eddie Cantor’s show, his latest discovery, Dinah Shore, had to forego her breakout hit, “Yes, My Darling Daughter,” in favor of an arrangement of the public domain “Listen to the Mockingbird.” A number of bandleaders simply gave up their network shows, some because they couldn’t eliminate ASCAP music from their repertoire, and others because they wouldn’t sign indemnity agreements demanded by the networks, who worried that copyright infringement claims would result if a rogue player were to “suddenly interpolate a few ‘hot licks’ of an ASCAP tune into an otherwise perfectly safe number.”

So it went for months, original BMI tunes alternating with old public-domain favorites like “Home on the Range,” “Polly Wolly Doodle,” and songs of Stephen Foster. “Jeannie with the Light Brown Hair,” published in 1854, is often said to have been the most performed song on radio in 1941. NBC banned Kate Smith from a Four-H Club broadcast, rather than make an exception for “God Bless America.” Even “Sharkey,” a trained seal act then enjoying a brief vogue, was barred from the air—his signature trick was playing “Where the River Shannon Flows,” an ASCAP tune, on a set of horns.

So it went for months, original BMI tunes alternating with old public-domain favorites like “Home on the Range,” “Polly Wolly Doodle,” and songs of Stephen Foster. “Jeannie with the Light Brown Hair,” published in 1854, is often said to have been the most performed song on radio in 1941. NBC banned Kate Smith from a Four-H Club broadcast, rather than make an exception for “God Bless America.” Even “Sharkey,” a trained seal act then enjoying a brief vogue, was barred from the air—his signature trick was playing “Where the River Shannon Flows,” an ASCAP tune, on a set of horns.

©2012 Gary A. Rosen